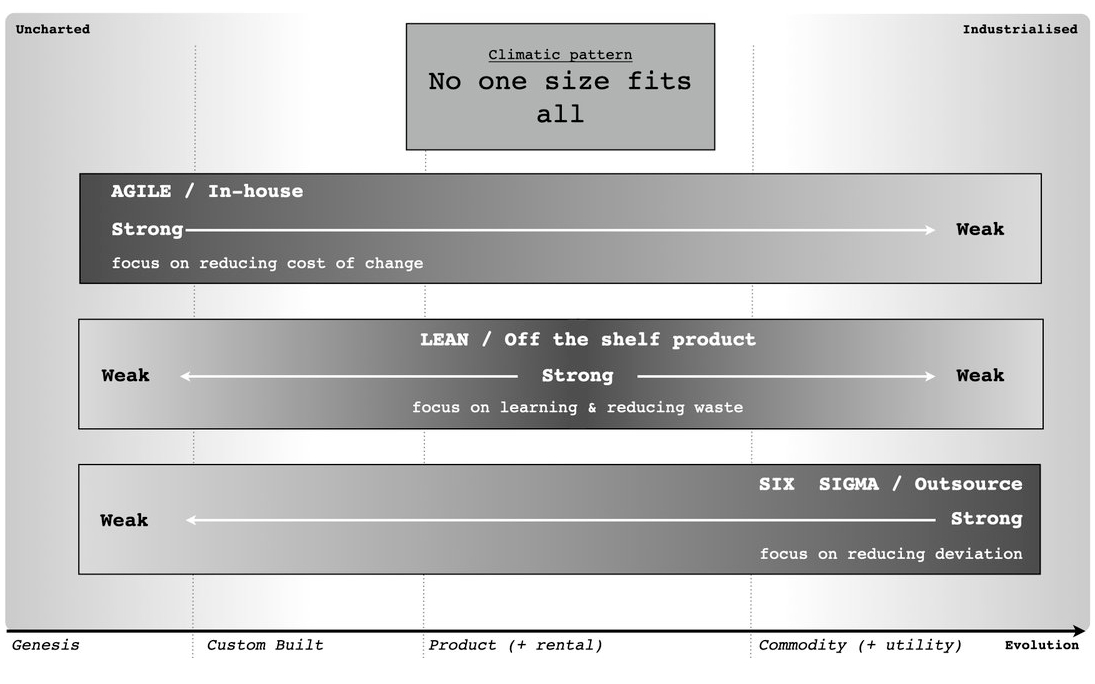

In the first post on Mixed Operating Models I discussed that each application in your landscape, both custom built and third-party will need a different type of operating model and using wardley mapping to map that landscape will give the context of which model is appropriate and at what time. Transitioning between models won’t be easy and requires both technical and cultural changes to be successful.

In this post, I will talk about the technical aspects that act as a foundation to any operating model change and cultural shift.

Step 1 - The hygiene factors

How mature is your current operating model? Are your releases frequent and stable? Do you have good measurement and metrics?

Before making any change it is always worth observing your current ways of working and seeing what is successful and what isn’t. What data you’re capturing and what you are missing - these are the hygiene factors. In particular when moving from an DevOps model to an ITIL model it’s common to look at two initial hygiene factors: metadata and the CMDB.

Metadata comes in a number of forms depending on how you’re looking at your estate: this could be tagging of infrastructure, code version tagging, database attributes or even standard naming conventions. Understanding the metadata, their relationships and cleaning them to ensure standardisation is an important (albeit sometimes long and drawn out) step to make sure you’re able to understand what is going to be impacted by the new changes.

This links very closely to the next key hygiene factor: the CMDB. The configuration management database is an element described in detail in the ITIL framework but can be implemented in a number of ways. In most large organisations this is an actual database, often part of a big vendor product that stores all the information about infrastructure, applications and their relationships. In other organisations I have seen this implemented as git repositories or even as a spreadsheet. In almost all cases, unless automated, it’s typically out of date. This is one of the classic criticisms of the ITIL CMDB - that it’s always out of date. Again, a criticism of the typical implementation, not of ITIL itself. The hygiene factor here is really: automation. Make sure your CMDB is connected to everything, automatically pulling in as many sources of information as possible in order to start building that complex web of relationships between infrastructure and applications and between different applications in the ecosystem.

NB: don’t boil the ocean on this one. Go down as far as you think you need. If you start getting into ingesting your full software-bill-of-materials into your CMDB then you’ve probably gone too far. There are other tools for that - and it’s turtles all the way down.

The purpose of this first step is pretty simple: know what you’ve got, then you can think about what to do with it.

Step 2 - Product Lifecycle

Every application in your ecosystem, whether installed or SaaS, cloud or on-prem has a lifespan and will sit within 4 stages of its lifecycle. The is linked to the Technology Adoption Curve (Diffusion of Innovations, Everett Rogers, 1962).

The language used to describe these four stages will vary depending to whom you’re speaking:

- Diffusion of Innovators - Innovators + Early Adopters, Early Majority, Late Majority, Laggards.

- In Wardley Mapping - Genesis, Custom-Built, Product, Commodity

- Marketing/Product - Market Development, Market Growth, Maturity, Decline

- Software development - Innovation, Growth, Maturity/Stability, End-of-Life.

Whichever nomenclature you decide to use in your organisation is irrelevant, what is more important is a good understanding of those 4 stages for each application in your ecosystem. As described in Part 1 - one of the key understandings behind wardley mapping is a representation of movement and that the economic shifts in the market that will force applications, infrastructure, data, knowledge and practices to move through these 4 stages irrespective of the actions of any organisation. Understanding this means that when looking at the product lifecycle for all the applications in the ecosystem - you have to be able to state in which stage it is actually in relative to the market, not the state that it is in inside your organisation or what state you wished it was in.

Understanding which applications are in the innovation stage and which applications are commodity, means you’ll have a better understanding of where Agile/DevOps methods fit and also where Six Sigma/ITIL methods are most appropriate.

Ensuring this product lifecycle is encoded into the existing CMDB information allows you to ensure you’re providing the right tools and practices for the relevant applications and which ones should be your next focus of transition.

NB: I’d like to see wardley map views integrated into ITSM products in the future if someone can build that please.

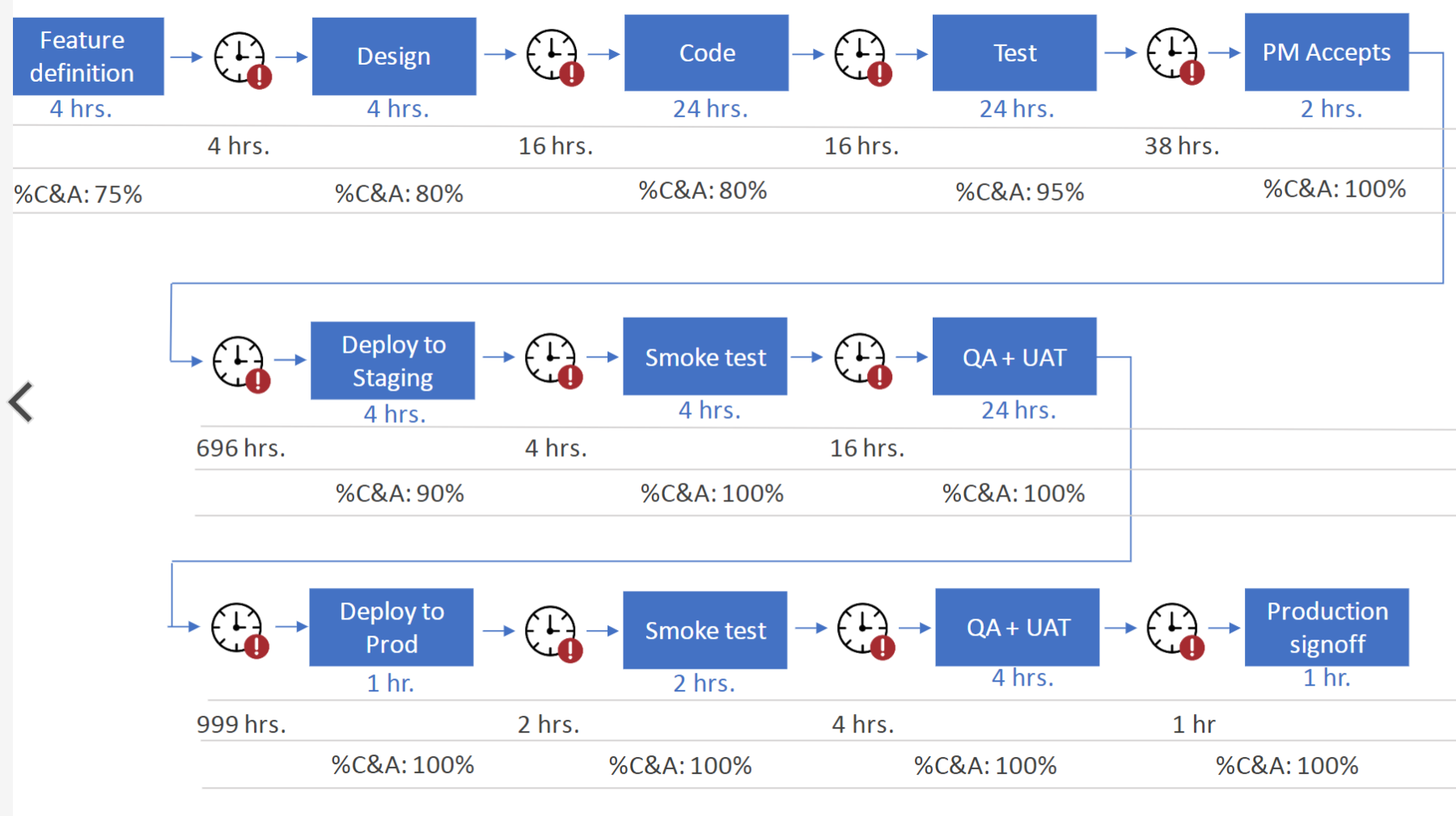

Step 3 - Value Stream Mapping

Value Steam Mapping (VSM) is a technique that comes from the world of lean manufacturing and has been a key element of the DevOps movement since its inception. The purpose of value stream mapping in a software development (or other knowledge work) context is to maximise the time-to-value by identifying all the steps in the process, both human and automated, measuring how long each takes and what the wait time is between each step. To quote Peter Drucker “You can’t improve what you can’t measure” so while it can certainly be straight forward to map all the elements of a process it can sometimes be challenging to measure each step of the process as it may requirement modification or addition of new tools. For DevOps practices VSM ties in with the Continuous Delivery practices in trying to maximise speed and automate the software delivery from idea to production.

Image source: The Most Important Tool in DevOps: Value Stream Mapping

Image source: The Most Important Tool in DevOps: Value Stream Mapping

The debate between Agile (”people over processes”) and Six Sigma (”process control and standardisation”) will rage on in corners of the internet until long after my career is over but like any battle between two opposing side there is a no-man’s land upon which both parties either agree or choose not to fight about. Value Stream Mapping appears to be that process upon which both sides agree. For the Agile folks it’s about speeding up their deployment pipelines and Agile practices and for the Six Sigma folks its about standardisation and reducing waste. Six Sigma always had process maps but most Six Sigma practitioners now focus on Lean Six Sigma which include VSM. Same methodology, being spoken about in different ways with different language.

Bringing it all together

So you’ve got a big list of all the applications in your environment in your CMDB of choice, mapped your application landscape (don’t worry if its imperfect - they always are) and you’ve got a value stream map for every application’s lifecycle? If you’ve really done all that you’re better than 99.9% of the organisations I have ever worked with. For the rest of you - bookmark this post and work through the steps, you’ll thank me later.

Understanding and keeping track of the lifecycle of all the applications and infrastructure components in your environment is no easy task - even if your environment is a set of neatly stitched together SaaS services. All applications are going to follow the technology adoption curve based on the market effects around them. Being pro-active about managing that lifecycle and modifying your operating model as the lifecycle changes is key to ensuring the smooth running of your business otherwise you’ll find yourself with a process that slows you down or a process that’s inefficient and not cost-effective.

I’ve been asked the question previously: When do you really know when to make the change?

The complicated answer is when the map tells you, however the rule-of-thumb that I’ve found to be useful is: when change is not regular and continuous then it’s stable. When its stable start shifting the model, writing stuff down, focusing on testing, reducing defects and managing risk.

You’ve read Part 1 and most of this Part 2 post now and you’re probably thinking that I’ve set the stage for a big shift in operating model. Us and them, right and wrong, agile and six sigma. Well, here’s the truth: both models share the same foundations, both models want to manage change, manage risk, speed up time to delivery. Both models want developers making changes through a pipeline that can be automated, measured and improved. Both models want to reduce defects and improve testing.

So here is the little secret - this post series is titled “mixed operating models” however the reality is that it’s the same foundation, the same objectives. The only difference (when you’re not ideological about it) is that the tools, the language and (some) of the process look a little different. Transition doesn’t need to be big bang - it can be a slow introduction of new ideas, new tools and small incremental changes - just like we do with our applications.

The journey here can be a long one, not only because of the time it can take to implement some of the steps highlighted here but also because of the culture shift that is required in tandem to this.

Next time … cultural change when the operating model shifts.